A building is a thinking tool

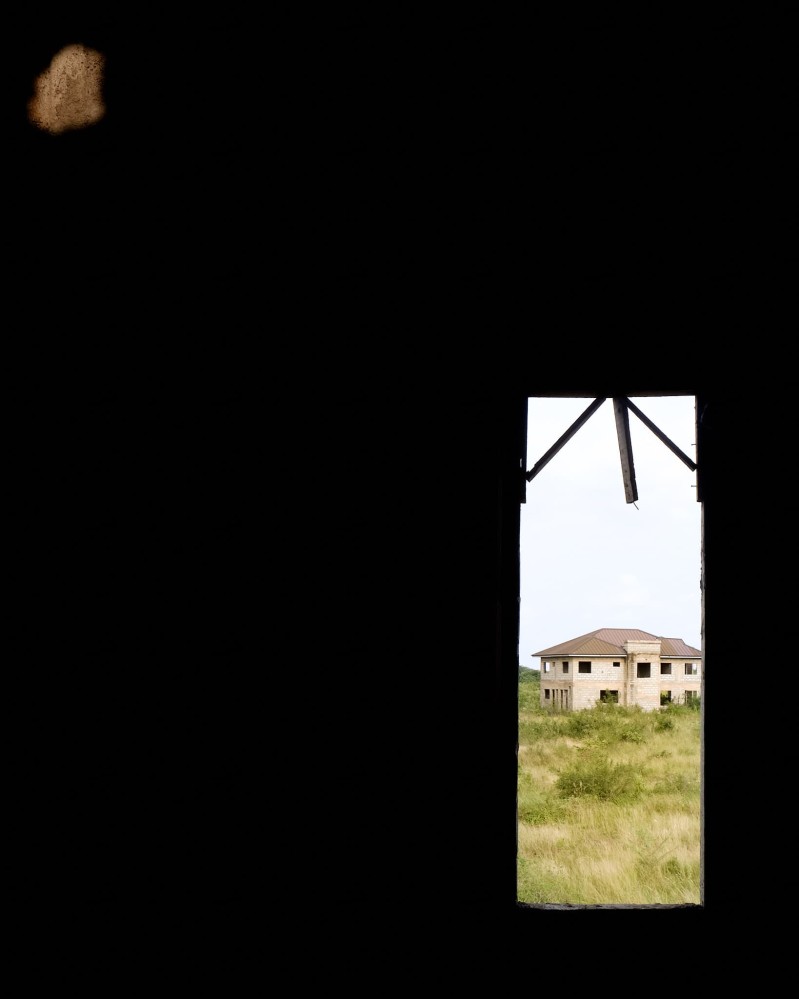

A photo essay on the first 10 months of construction of our family home. Also, on the idea of architecture as a way of knowing.

We began construction on our family home in January 2022. We’ve made a lot of progress, and this post is a photo essay documenting the first 10 months.

I’m also going to attempt to articulate something else.

Going into this project, I knew that I would come out on the other side with a more practical understanding of how buildings come together. What I hadn’t anticipated was how it would also change me in more fundamental ways.

What began as an emotion-driven search for home also became an intellectual journey that has changed how I see and interact with the world. I feel a different person than I was 10 months ago. More calm, more thankful, more introspective, and more confident in following the quiet counsel of my intuition.

If you’re mainly curious about the progress of the house, you can skip to the photos and read the photo captions for context. The photos are in roughly chronological order, and they’re a mix of my brother Alfred’s professional photography and my own amateur phone shots (all the really nice photos are his 😀).

But if you’re also curious to go deeper, the surrounding essay explains how the theoretical foundation of the project has evolved since construction began. While the photos sometimes line up to resonate with the text, other times, an image won’t have any connection to the paragraph that came before and after it. Think of the words as something like accompanying music - you can move the text to the foreground or background of your experience.

There are two central claims in the essay:

- That observing how architecture interacts with the world can reveal to us how things work

- That architecture can shape the kinds of thoughts you’re able to think

(As a refresh, here’s the project brief before we began design, here are detailed design notes, and you can find all my writing about the family home project in one place here.)

Architecture as a way of knowing

How do we know what we know?

How do we know that a type of fruit is okay to eat, or that someone can be trusted, or that a certain combination of chemicals cures disease?

There are several paths to understanding the world, including sense perception, reason, and more, and something special happens when we approach even the seemingly mundane aspects of life as a path to knowledge.

Take cooking. What does it mean to approach cooking as a way of knowing?

Rebecca May Johnson asked herself this and shared her answer in What Happened When I Began to Treat Cooking Like Thinking (paywall).

The lessons of the kitchen are the same lessons we pursue in literature, philosophy, politics and science, yet the way that cooking is treated in our culture is so different from the way these apparently serious subjects are treated… what if I allowed philosophy into the kitchen? What would I discover if I treated cooking as thinking?

Some ways of knowing help us understand by showing us a sketch on a small scale, so that we can extrapolate that small lesson into a larger insight.

For Johnson, the simple act of adding garlic into sauce was the vehicle through which she was reminded that, modest as they might seem, her actions do have a perceptible impact in the world. It was a reminder of her agency.

Our actions can alter the world around us. The way I treat a clove of garlic does not just change its size but its chemistry: cutting it breaks down cell walls, triggering enzyme reactions. The decision to dice or slice or crush it will shape the entire flavour of the meal I am cooking. And we have not even begun to discuss how the garlic is applied in the pan: is it added to cold oil? Is it added to a hot pan? Is it a late addition to a sauce? Each of these methods has a profound impact on the outcome. Cooking can show us this: that our actions matter. Even a simple recipe can reveal the way our interactions with the world can change it, and through this we are changed too.

Returning to architecture. What does it mean to approach architecture as a way of knowing?

It means to pay attention to what architecture can tell us about the forces that shape it. A window’s size might imply something about that culture’s views on privacy and modesty. The angle of a roof’s pitch and the depth of its eaves might imply something about an area’s climate. Certain wall materials might imply something about the global supply chains to which that community has access, or which materials are most abundant in the surrounding area.

A building can be a mute teacher from which social, economic, climatic, and several other forces can be inferred.

Beyond even this, architecture can teach us about other even more fundamental forces of the universe. Consider for a moment, a definition of architecture that is broad enough to describe both man-made buildings as well as structures found in nature that imply shelter and enclosure.

A dreamer observes how the large tree trunks hold up the ceiling of the forest. Through trial and error, they’re able to infer some of the principles of gravity and compression, and put those principles to work in the technology that becomes known as the column.

Another dreamer observes the surprising strength of a bundle of branches leaning against each other. That observation begets an inkling begets a hunch begets a hypothesis begets the understanding of lateral forces that finds expression in the technology of the flying buttress.

All of which is to say, when a human being observes the way an upper floor cantilevers over its base, or let’s themselves be mesmerised by the strange quality of light that occurs when it filters through warped glass, simply observing a line or motion across space triggers that part of our pattern-making brain that asks, “I wonder why…”

We are sensing beings. We can’t help ourselves. We see patterns all around us, and our minds are optimised for story and metaphor, which allows us leap from observation to inference, towards a deeper understanding of the world around us. We’re like children, where life itself is a scavenger hunt organised by the universe, or one of those connect-the-dots-to-create-a-picture puzzle books. And given that we’re surrounded by architectures, it’s not so surprising that those very architectures become a path to understanding the world.

Scientist and physician Simon Flexner said “Ideas may come to us out of order in point of time. We may discover a detail of the façade before we know too much about the foundation. But in the end all knowledge has its place.” And while he was referring to medical research, I love the architectural imagery in this statement, in how it invites us to take comfort that even when something does not make sense immediately, it is right and proper to simply pay attention.

In the harried distraction of our lives, we might sometimes find a moment of architecture that breaks through, which makes us pause. It’s an image on Pinterest, or a photo in a magazine, or if you’re very lucky, you’re in the space in person. You find yourself thinking that there is something…interesting, about this space. You don’t have the words to explain it. The idea is just right around the corner, frustratingly out of sight. Asked to explain why a specific space is interesting, you’ll find that your words have marooned you.

This is fine.

Because while we might lack the grammar, for now, to explain why a shape, or a form, or a quality of line, or a species of wall, or a flavour of light is important, it’s enough to recognise that the Thing at the back of your mind, the part of you that sees the patterns in things, glimpsed a fragment of something, and came close to grasping it. With luck, we might one day be able to follow that thread towards a deeper understanding of some part of the world. For now, it’s enough to simply Notice.

“See first, think later, then test. But always see first. Or, you will only see what you were expecting. Most scientists forget that.” - Douglas Adams

A building as a tool that aids thinking

“The tools that you use shape how you work and, to some extent, what you understand to be possible…” - Evelyn Bi, On Object Freedom

Places and objects embody values. They carry ideas.

A highly ornamented formal dining room in a French château might be pregnant with ideas of tradition, while the ascetic sparseness of a Modernist bedroom might speak to ideas related to stoicism.

Which is to say, a place can tune a mind in harmony with the ideas embedded within it. Enclosed within its womb, one might find that it’s easier to access certain thoughts, while other thoughts feel further away. As Jason Snyder phrased it, “Places physically shape your cognition” which is why it’s important that we’re intentional about “crafting our context” (as described by Jay Cousins).

At some point during construction, when it became clear that we could actually pull this off, I began to think more deeply on which thoughts I wanted our home to make more easily accessible.

It was like a mental switch flipped in my head, and I realised that a building is an instrument that you can tune to amplify the ideas you want to surround yourself with. In the same way a pencil can be a thinking tool, or a calculator can be a thinking tool, I realised that a building, too, can be a thinking tool. My ambition for the project grew.

Previously, the animating question for the project had been “How do we build a home that embodies care?” As the building went up around us, I also began to ask “How do we shape a building into a lens through which to understand the world, or a prosthetic for the mind?’

How did the design evolve in sympathy with this question? To be honest, there weren’t any dramatic changes; we didn’t blow up the floor plan. Instead, thinking in this way helped me feel more confident about decisions we had made a long time ago.

For example, very early in the project, we decided to have a formal office (which we called the study), and a separate creative space (which we called the studio). I couldn’t articulate at the time why it was important to have these be distinct spaces, just that it felt important. Now, I realise the value in having different spaces for different kinds of work. The study for “laptop stuff” and the studio as a creative space where it’s okay to get things messy.

Another decision I’m glad we went through with, was to have a dedicated guest bedroom. We came close to eliminating that room in favour of a “flex” space, but I’m thankful we have a dedicated guest bedroom which makes it a lot easier to host friends and collaborators who might be looking to disappear for a long weekend (or a few weeks) as they work on something.

Maybe the biggest impact this new thinking has had is around how I’ve been thinking about ornament and landscape design.

I have a lot more clarity in my mind about the kind of artwork I would like in different spaces, for example, and in speaking with the landscape architect, it’s now more obvious which landscape moves are preferable, and why.

As the house comes out of the ground, it’s become easier to imagine living there, and it’s also become easier to imagine who I want to be in this space.

Is it arrogant to confess that I find myself hoping to be able to provide a sanctuary not only for my family, but for friends working on and thinking about interesting things?

I hope we succeed in tuning the building into a space that invites deep thought and introspection, where the building gives people permission to take fleeting ideas seriously. I want our space to be one that helps people think more clearly. I want friends spending the weekend while they think through something. I want long debates that go into the early hours of the day. I hope we can tune the space into the birthing place and cradle of several first drafts.

A building as a thing that thinks

Something I knew passively, but hadn’t been prepared for, was how quickly the building would acquire personality as it emerged.

The higher the walls get, the more it feels like a person coming into being.

I confess that I find myself really taken by specific parts of the building. Certain moves that I hadn’t paid much attention to when the building was still a drawing have became my favourite parts of the project, and I’m sure my favourite areas will continue to change.

Another confession: I have very literally found myself getting randomly shy and hot-faced around a particular stretch of wall. I know this is an absurd thing to say, but it’s true 🤣

All of a sudden, “What does this building want?” no longer feels like a ridiculous question. It feels the most natural thing in the world to be crawling over the sleeping body of this house-sized giant and feel, intuitively that a certain design move is more in harmony with what the house “wants.”

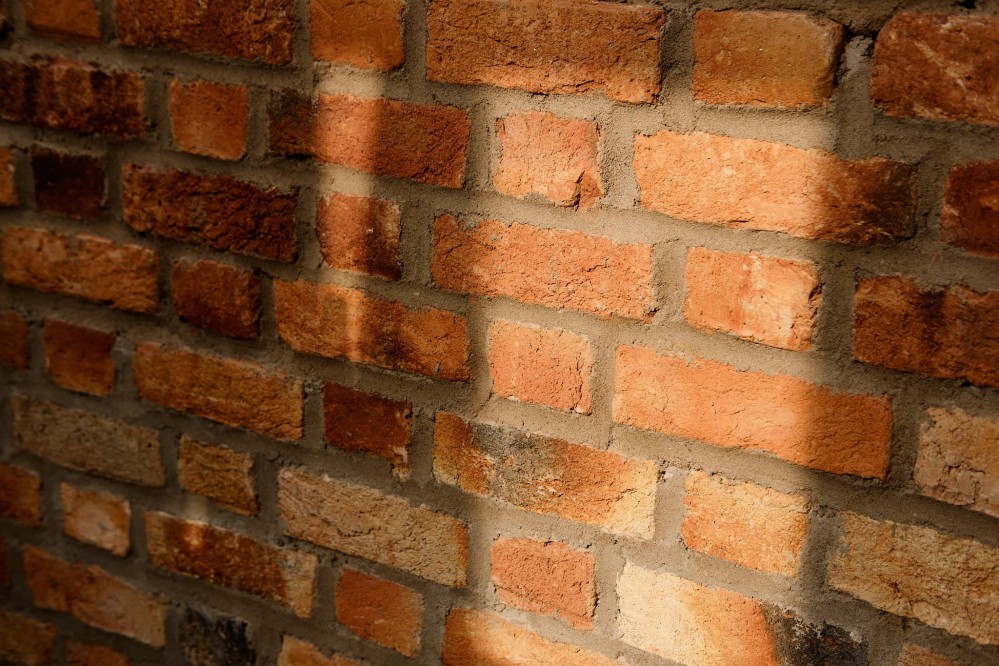

Another thing I was not prepared for was how different the brick looks under different light. This thing changes colour. Like skin.

Right before rain, when the sky is overcast, the bricks look a restrained dusty brown-grey. At high noon, they become a scalding silver-orange. Near evening, dappled light radiates off the brick like a flame turned down low, like a slow fever under blushing skin.

I know on some level that it’s my pattern-seeking brain that’s making me read things into matter, but what I also know is that as the building has emerged, invoked into being by the intent and density of focus of many minds and hands, it has began to acquire a certain flavour.

What happens when you take seriously the idea that different buildings can have different personalities? That a building can have a mood. A disposition.

When we do site visits, when no-one is watching, I will surreptitiously pat a warm hand against his side, as one will do for a cat, as a comforting gesture. I like to think he’s mostly still trying to figure out what to make of all of us.

I find myself wanting to visit the site a lot, to do nothing more than to sit in the lap of the courtyard while he sleeps. It’s the same part of my brain that misses good friends. I don’t know what to make of this feeling towards an inanimate thing. I’m very curious to see how it evolves as the house progresses.

“The ways we use our tools inform what they can be, not just the other way around. How one perceives an object imbues it with life and, in return, it serves as the concrete manifestation of the capacity it’s given.” - Evelyn Bi, On Object Freedom

The project has not gone off without challenges. We’re a few months behind schedule. The cedi has fallen off a cliff, and everything is a lot more expensive than we budgeted for (I purchased a laundry tub for 300% more than the initial price I saw a few months ago).

But overall, I’m thankful and relieved. All things considered, the project has been relatively smooth. Ten months in, we work as a team to resolve challenges as they emerge, each one a learning opportunity. We take it a step at a time, confident that we’re making something special.

Thank you for your interest, and if you have any questions, feel free to reach out on Twitter, or through the form at the bottom of this page.

(If you enjoy my writing and want to support my personal research projects, the best way is to buy me a book!)

-

Family Home

-

Family Home

-

Family Home